Ruby was born on November 29, 1910, in the mill town of Monohon. Monohon was located on the southeastern shore of Lake Sammamish.

Ruby's full name was Ruby Barbara, and she picked up the nickname Ru-barb as a girl. She was one of eight children. She was a bright child and was able to read before she started school; her father taught her by having her sound out the words she saw and asked about. Ruby was also born with cataracts, which affected her ability to clearly see color. She lived with the cataracts for most of her life, although she wore glasses, which helped some.

Ruby's father, Thomas Edwin Howatson, was born in 1883 in Quebec. His parents were from County Ayr in Scotland. He was known as Ed, and worked in the Monohon Mill as well as the woods. When he worked in the woods, he drove a team that pulled logs out. Ruby described him as " a very warm, caring parent– if he sat down anywhere, there would always be a kid on his lap". Ruby's mother Elsie Peck was born in 1888 in Kentucky. Her family emigrated to Seattle in 1889 and initially settled in Fremont; they moved to Monohon after people in the town government told Elsie's father that he could no longer keep his cows there. Elsie married Thomas Howatson on December 11, 1907 in the home of Elsie's parents --- the Peck family owned 80 acres located off 212th Avenue. Ruby said the Pecks were descended from early American settlers; the family had been in America since emigrating from Germany in the 1630s. Ruby attended the two-room schoolhouse in Monohon in the 1910s and first half of the 1920s. There were four classes (grades) in each room. Though cars were becoming common in our area by the time Ruby was a girl, the roads were still very much for the horse and buggy– they were simple one lane dirt roads with deeps ruts that filled with water when it rained. Ruby transferred from the Monohan school to Issaquah High School in 1925 after fire destroyed Monohon. She graduated from Issaquah High in 1928.

When interviewed several years before she died in 2003, Ruby recalled that the children of the period were very creative and inventive. She said "they were dirt poor but never felt deprived." Ruby said they had a great full fun life with much love. They created games out of anything that was available to them. One was fish, using the leaves of ferns as the fish. Gunnysacks were used as hammocks; the sacks would be taken apart at the sides and bailing wire woven in and out at either end and tied to trees. The children would sometimes sleep out in them at night in the summer, the sun would wake them early and they were not allowed in the kitchen until the mill whistle blew at 7:30 in the morning. Ruby also told the tale of the time her mother once made a ball and bat for the children to play baseball. She simply took a stick and carved a bat on the spot. The ball was made from a square piece of rubber from the heel of a shoe and a Rockford sock was wrapped around the piece of rubber for cushioning. Denim was placed around the sock to firm it up and presto! they were ready for a game of baseball. The children would often walk to meet their father in the woods and walk home with him. They would take a bag with them to gather wood from the stumps. Ruby said there was a reason for this. The thick bark from the trees held a fire well and was excellent for cooking bread. Anyone who is familiar with Eastside history knows about the fire that devastated Monohon on June 26, 1925. Ruby was 14 at the time and witnessed the fire. At the time of the fire her mother was gone, visiting her own mother. Ruby was left to watch the other children. One of her brothers had poured water on her, and she had chased him up a tree. Once up the tree he announced there was a fire burning Monohon, and indeed there was. The children were placed in a wagon and taken to their grandparents' house. The community pulled together to help one another save what they could from their homes.

Ruby recalled that in those days "everyone owned a cow that provided milk and butter. They baked their own bread, and had a garden." This resulted in lots of chores needing to be done, both before and after school, and all children were expected to do them. For entertainment kids created "very inventive" games, as Ruby described above. As she got a little older, more adult entertainment was available: Ruby had fond memories of dances that were held in the 1920s on the second floor of the Skogman house (now known as the Reard-Freed House).

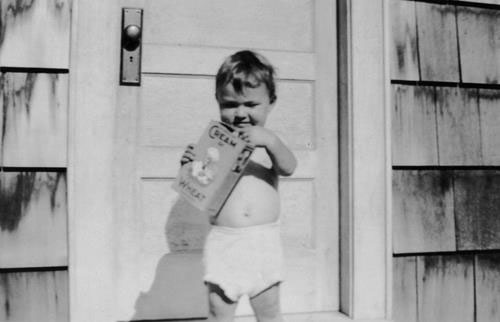

Ruby married Floyd Eddy on May 4, 1928. (Floyd's family owned a 10-acre farm just southeast of SE 4th Street. on 218th Ave. SE. The house–built after the original home burned down in August 1920--- is still in use as a residence and appears very much the same as the day it was built). Floyd and Ruby eloped, which caused quite a sensation in both their families and the community. Ruby and Floyd purchased one acre on the southeast corner of NE 8th Street and 228th Avenue NE, where Safeway is located today. This area is now known as Highland Center, but in the 1920s and 1930s (and probably for some time after) it was called Four Corners. At the time Ruby and Floyd purchased the property, there was a one-room schoolhouse located on the corner. The schoolhouse had performed many uses for the community over the years before it became home to Ruby and Floyd. It was not only a place for children to learn their lessons, but also a place for the community to gather for dances and meetings. Ruby and Floyd lived in the schoolhouse until their cottage was completed. (The schoolhouse was then converted to a chicken house.) Their new home was completed just before the birth of their only child, Donald, born December 3, 1934.

Ruby and Floyd eventually acquired 20 acres of land on the corner of NE 8th Street and 228th Avenue NE. In 1943 they purchased property off the Redmond-Fall City Road, which would be their home for over 50 years. Ruby lived there until she died earlier this year. They ran dairy cattle, then beef cattle, for many years, and Floyd also started a wholesale nursery business. Floyd was also known for his skills as a water-witcher (or dowser), and could tell where and how deep to dig water wells that people were constantly needing in this area before plumbing was available. Floyd taught this vanishing art to Ruby.

Ruby said their house was built in 1892-93 by a Swedish bachelor. There was no running water there for many years, though Floyd eventually put in plumbing. Until very recently the house only used a wood burning stove for heat. Ruby routinely chopped wood both for this stove and for the cook stove she used to cook her meals on. A gas stove wasn't installed in the house until 2001, after Ruby had had a stroke.

Floyd died in 1990, but Ruby continued to live at the house on Redmond-Fall City Road for most of the next 13 years. She died at home on April 9, 2003, at the age of 92. A service was held for her in Fall City on April 26. Folks attending were asked to wear jeans and a plaid or flannel shirt "in keeping with Ruby's standard workday attire. Her family read some of her poetry (she was an avid writer) at the service.

Ruby's life was summed up in a poignant article written by veteran reporter John Hahn of the Seattle P-I. In the April 24 issue of the P-I, Hahn wrote about an interview he'd had with both Ruby and Floyd before. He told how he had described them as "Burns and Allen in Oshkosh overalls" when he met them some 20 or so years ago. Hahn also told several funny stories that Ruby's son Don had shared with him about Ruby, and one of those stories is worth repeating here: "Ruby (was) washing dishes at the kitchen table, beneath a single hanging light bulb, when Floyd, who was separating raw milk nearby, hollered about a particularly loud clap of thunder. He came around the corner just in time to see lightning leap down from that light bulb and into the top of her head! All she got from it was a terrible ringing in her ears." And then, admiringly, Hahn added: "One tough old broad."

— Virginia Kuhn and Phil Dougherty